Pricing Innovation and New Product Development with Kyle Westra

In this episode of our The Innovation Room podcast, we’ll be focusing on a very important and interesting, but often challenging and misunderstood topic: the pricing of innovation and new product development.

Pricing is a cross-functional and extremely powerful tool for not just driving and optimizing profitability, but also for determining the feasibility of an innovation early on.

To help us better understand the topic, we have Kyle Westra with us. He currently works as a manager for Wiglaf Pricing and has actually written a book called The New Invisible Hand on the topic.

Table of contents

Can you tell us about you and your background?

KYLE: Sure, thank you Jesse for having me. My name is Kyle Westra, and I'm a manager for Wiglaf pricing. We're boutique pricing consultancy that helps executives manage price better. Often times that means figuring out the right pricing for new product development.

My background is actually more in international relations and economics. I worked in foreign policy for several years before getting my MBA and moving into digital business and pricing strategy in particular. I've been doing pricing strategy for just about six years now.

What is pricing?

KYLE: Historically, pricing has been a subset of marketing and hasn't received enough focus on its own. And one of the issues with that is that it hasn't always gotten the right feedback from other parts of the organization.

So, an important part of modern pricing is to act as that interstitial person within organizations to collect information and feedback from lots of different stakeholders and then figure out how to get everyone rowing in the same direction together.

In terms of pricing and new product development in particular, I suppose I've long had an interest in entrepreneurship. I've worked for a couple of small startups and am just interested in how markets and economies develop, and innovation is obviously such an important part of that.

From the pricing perspective, innovation is really where pricing can help set the stage for maximum success.

Not just on what the pricing strategy should be at a high level, but the pricing model too: is this a one-time sale? Is this a subscription? Is this usage based

And then the pricing metrics: per person, per megabyte, per square foot?

And finally, the actual price points themselves. So, the dollars and euros associated with what the customer actually sees. Pricing is often considered as just that last point, just the price points, but it's really this entire macro to micro process touching so many different areas within the organization.

Pricing is often considered as just that last point, just the price points, but it's really this entire macro to micro process touching so many different areas within the organization.

One of the reasons for pricing being so important for new product, service, or offer development is that you really only get one shot before you reach the market.

Once a price, or a pricing structure, is out there, it's a lot harder to change it. Once customers are starting to become accustomed to how it has been sold, once they get anchored on the price point that you introduce it with, it becomes a lot harder to change things after the fact. So, putting in the time, effort and energy required to get pricing done right before the product hits the market can have a big impact.

How do you define pricing as a concept?

JESSE: With pricing being such multifaceted field, how do you define it? Where do you draw the line between business models and pricing, especially for new products and innovations?

KYLE: Well, I think because they're so closely related to each other, you can't really draw firm lines between them. Clearly, an important part of the business model needs to be a sense of the price, pricing and how you anticipate selling this in a profitable manner.

So, this idea of baking in profitability from the beginning, already having a sense of what types of customers you're looking to serve, what problems they have, how different customers might value your offering differently from one another, are all key questions related to pricing.

Customer segmentation and price segmentation should, from our perspective, be a really critical part of the entire product development process.

Otherwise, you might spend years developing something that people really don't want – or where there's no way to sell it profitably. And, if you can’t sell it profitably, then you don't really have a business.

What makes pricing so difficult specifically for innovations and new products? Is it that there’s no real data available for a new innovative product?

KYLE: You're absolutely right. That is one of the benefits of re-pricing and having pricing as a continuous process after a product is launched – and were certainly in favor of that, it’s something that companies must do well in order to stay relevant.

One of the advantages at that stage is that you have a lot more market feedback and a better sense of how your competition is reacting, so you have a lot more external data to input into your models to better understand the market:

- Are you correctly understanding the value that you're creating for your customers?

- Are you capturing your fair share of that?

- Is your pricing helping your sales cycle rather than being an impediment to it?

During new product development and innovation management, you're a lot less sure, on a fundamental level, on how customers and competitors in the market are going to perceive the product.

What we try to do as an initial stage is to think more about price estimation rather than price clarification, or actual market pricing.

It's okay to start at a broader, less granular, level and get at least some sense and an estimate of what we think this product is worth for different segments of customers.

How can we capture some of that value? What type of a model enables us to grow our revenue and our profitability as we grow the number of customers?

Start at a broader, less granular, level and get an estimate of what the product is worth for different segments of customers.

When we go through the pricing of new product development, the first stage is based on internal understanding. Sometimes, for a completely new innovative product, that might even be the best you can do: different executives representing different parts of the company that are familiar with the customers.

They get together in the same room and hash out what problems we are trying to solve. How does our product address those problems better than the alternatives? Keep in mind that the alternative might simply be to do nothing. The customer always has a choice to buy your product or not. So, instead of Excel, they might just use pen and paper rather than an alternative spreadsheet application, for instance.

But starting internally, you at least can get a good initial draft on what the value on the table is.

That helps you get a sense of if there is a market opportunity there or not. From that point, it's easier to identify the known unknowns, the areas where you could use more information.

And then at that point, voice of customer research or other methods of addressing the actual market can be useful for further clarifying some of your assumptions and getting more detail and granularity to the actual prices that that your customers might be willing to pay.

How do innovators normally do pricing, and how do you recommend your customers do that?

KYLE: Well, I would separate how the process normally goes from how most people should address it.

Unfortunately, a lot of the time, especially for younger companies and less experienced executives, although it can be this way in very large companies as well, they tend to leave pricing decisions until the very last minute and just kind of slap a number at the end or look at what the competition is doing and simply copy their number.

The problem there, of course, is that you're running a really dangerous risk of undervaluing yourself and the product or service that you're offering, especially if it's something for more of a premium early adopter market. Those tend to be the types of customers that are less price sensitive and willing to pay a premium, so being able to capture higher margin and higher value from those customers also enables you to fund further investment and development down the pipeline.

So, the biggest mistake is not thinking about profitability early on and not putting the time and effort required into thinking how you can make pricing a beneficial attribute for this product, something that helps customers interact with it and purchase it – rather than something that stands in the way as a barrier between customers and the product.

The biggest mistake is not thinking about pricing and profitability early on during the product development.

We work with both very large and very small companies, and in broad strokes the way we recommend all of them to approach this is to do price estimation in the early phases and then price clarification later on.

Price estimation

Just the price estimation, a relatively rough cut, is often good enough to decide whether to go ahead with the product or not.

The main tool used for that is something called the Economic Value to Customer or EVC. That's a quantitative methodology for determining what the value drivers of your product are to the customer, and what the differential value is compared to the alternatives. So, in what ways is your product better and in which ways is your product worse, and then totalling that up into a comparison.

Customers always have alternatives, so they’re always making comparisons. A lot of times for innovation, we're aiming to create more value than the competitors, but it's just as legitimate to create something that's lower value and consequentially lower price as well. Something like EVC is a great way to figure out where you are.

The worst situation is thinking that you have more value than the customers, and then when you're actually crunching the numbers, realize you aren’t.

The worst situation is thinking that you have more value than the customers, and then when you're actually crunching the numbers, realize you aren’t.

In that case, you’d need to completely rethink the types of customers you address, or maybe rethink what constitutes the product that you’re trying to create in order to reach that value advantaged position.

Other methodologies that some of the viewers might be familiar with are called the Gabor-Granger Method and Van Westendorp Price Sensitivity Meter. These are complicated names, but they are simply methods to approximate what customers might be willing to pay for your product.

Those two in particular, rather than being internally focused, are external. So, you're going out to the market and using different survey methodologies to basically ask your customers, will they be willing to pay this amount of money, or this amount, or another one to get a sense of where you could be in terms of price bands or ranges.

The weaknesses of those methods are that:

- You need to have the time and money and put in the effort to go out and do market research

- There are fundamental biases in asking someone what they think they will be willing to pay.

And those biases are especially big for innovative new products.

For example, when someone first saw an iPhone and didn't really know what to do with it, if Apple had simply asked people what they would have been willing to pay, they would have really sold themselves short.

There are fundamental biases in asking people what they will be willing to pay, and that is especially true for innovative new products.

So, while those can be useful puzzle pieces, the danger we see is that sometimes people treat either of those methodologies as the be all and end all when they’re really more of a starting point.

We actually used those in my MBA class. We were tasked with figuring out what the price of a cup of soup from the cafeteria should be.

We’d identify different potential price points, do research, and at the end, come back with an answer that cup of soup should be between $3 and $6.

Great! Well, I guess that’s some information, but it’s still quite a large range, right? It says nothing about where in that range you should fall, and that's kind of the range that we probably could have guessed beforehand by just looking at what the competition is out there, and just with our own gut sense.

So, it's really a question of whether those tools will add to your understanding, or just confirm what you already know.

Price clarification

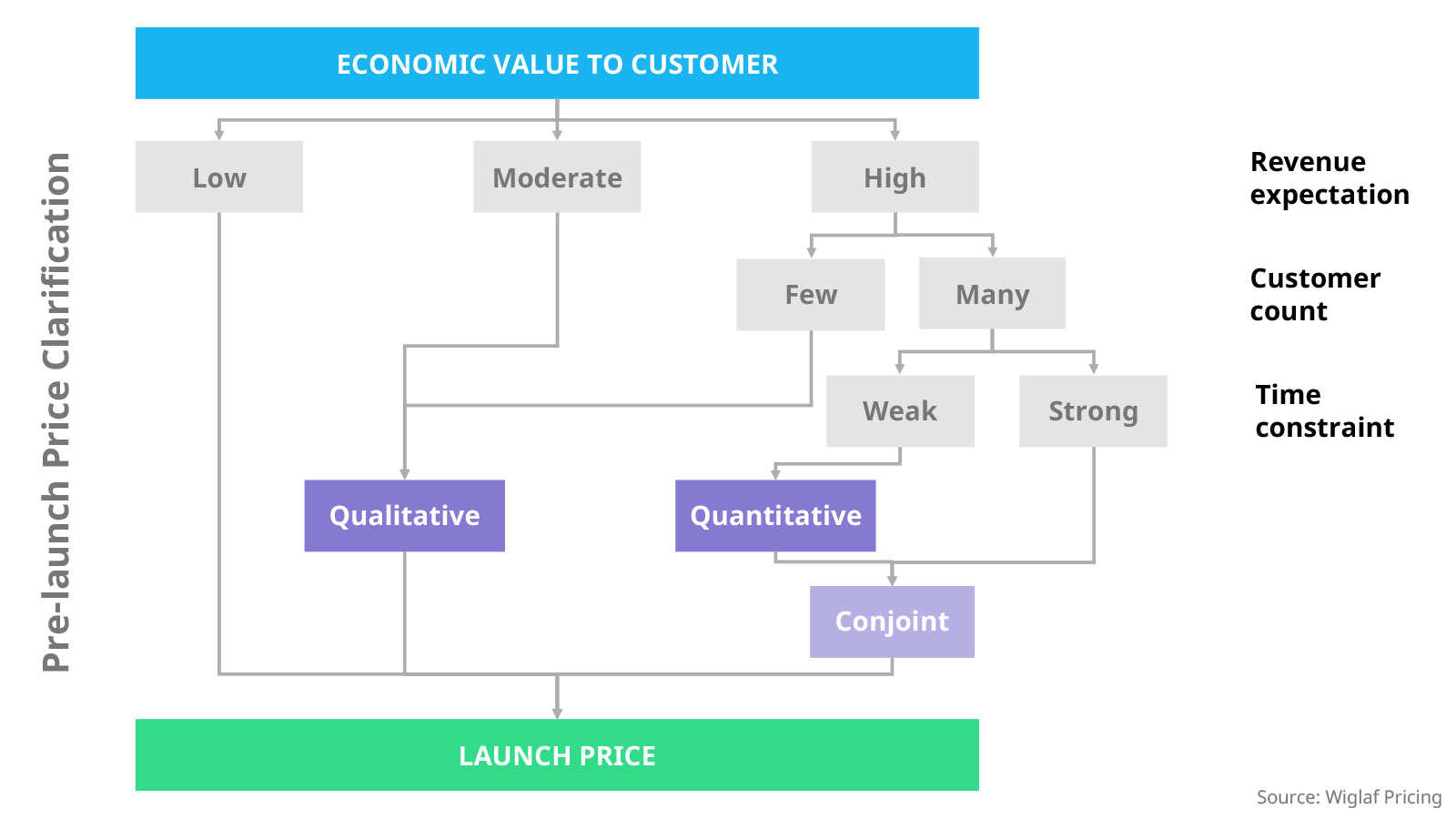

Once you've decided that it looks like there's something profitable here that we should pursue, it’s time for price clarification.

That's where your choices start to form a decision tree based on what your revenue expectations are for the product, how many customers you think you're going to be addressing and how much time you have until launch.

Depending on the answers to those questions, perhaps the best path is simply to refine the economic value to customer, the EVC that we've already developed, or sometimes it could be doing additional voice of customer market research. Whether qualitative or quantitative, it can be useful in informing your models. Then, at the highest range of those questions, there's a really great methodology called Conjoint analysis, which is not new, It's been around for decades, but it's the best method for getting a quantitatively defensible sense from potential customers of how they value different parts of your product.

Then, at the highest range of those questions, there's a really great methodology called Conjoint analysis, which is not new, It's been around for decades, but it's the best method for getting a quantitatively defensible sense from potential customers of how they value different parts of your product.

So, where the Gabor-Granger and the Van Westendorp depend on customers telling you what prices they'd be willing to pay, conjoint analysis has a nifty way for actually being able to tease out the implicit values and assumptions that customers are making when they choose between different products.

I won't go into more detail, but it removes many of the biases of those previous methodologies, but it takes time, effort, and money. And it's also really geared towards certain types of products where you have parameters or features that you can adjust in a comparative way to figure out what the relative value of each one of those features is.

JESSE: So more for software and services, and perhaps not so much for simple widgets?

KYLE: Exactly.

What are some common mistakes innovators do when it comes to pricing?

One of the biggest ones is around the pricing model and the pricing metrics that I already referred to.

So, it’s often less about the actual price and more about the method by which the price is charged.

Let's just take the case of a subscription. Is it per user? Is it per hectare? Is it per gallon?

Figuring out what the right metric that aligns as closely as possible to the value that the product or service is delivering is key. That way as you’re providing more value and the customer is using your product or service more, you're getting more in return.

Figuring out what the right metric that aligns as closely as possible to the value that the product or service is delivering is key.

The opposite of that would be, for instance, this one productivity software subscription priced per user.

So, if you think about it, it's a productivity software. If they're doing their job well, fewer users over time will need to use it. If they're charging per user, they're actually cutting themselves off at the knees, they're creating their own headwind.

So, the better job they do, the less money they make. And I think we can agree that that's not what we want, right?

Not only is that not what we want as innovators, but it's really confusing for customers too, customers aren't stupid. If they see something like that, it creates dissonance and confusion on the customer side as well.

And if it's such a problem that it's affecting your core profitability and revenue numbers, then you can't survive as a company and your customers aren't going to like that either.

So, really thinking through in what ways are we creating value and how can we align that from a value-based pricing perspective. Not only our pricing models and our metrics, but the price points as well. I think that’s one of the key issues.

Another one that I talked about quite a bit in my book, which is called the New Invisible Hand, is this issue around pricing transparency and how it can be used to better address your customers and emphasize the brand statements and marketing strategy that you want to make.

One of the interesting cases there would be Uber, the ride hailing company. Over the course of their lifetime, they've had difficulties in explaining their surge pricing to customers. They have gone through, and I'm sure will continue to go through, iterations of showing what the multiplier effect would be, in terms of percentage, in terms of dollars, not showing the multiplier at all but showing you what the end price will be, or simply notifying you that surge pricing is in effect, but not seeing any numbers behind that.

The constant question they were trying to solve is, is how do we communicate this fairly and honestly to customers without being a hurdle to them understanding and using the product? The dangers of bad communication and lack of useful transparency in general are to hurt your brand and turn off customers, and that was the case for Uber as well. It’s even invited regulatory scrutiny for them.

I think Uber has improved a lot in this. What they've landed on, for now at least, is to have decided, I think correctly, that customers don't really care about seeing the multiplier. They don't really know what to do with it. What does mean if prices are 1.2 times higher than normal or 1.3 times higher than normal? What I care about as the customer is, what is it going to cost me at the end. So, what they do now is to show what this ride is going to cost you to the very dollars and cents, and if you've taken roughly that right before, you will know if that is higher or lower than usual. But there are no more surprises for you. You don’t have to know that the normal cost of the ride is this, but now it's times 1.3 and then there is a surcharge for this and that. So, there's much less confusion about the end price. That's what I call price transparency.

So, what they do now is to show what this ride is going to cost you to the very dollars and cents, and if you've taken roughly that right before, you will know if that is higher or lower than usual. But there are no more surprises for you. You don’t have to know that the normal cost of the ride is this, but now it's times 1.3 and then there is a surcharge for this and that. So, there's much less confusion about the end price. That's what I call price transparency.

Note that they've actually decreased pricing transparency. It's less clear from the outside how they're arriving at that number. It's a black box. But the end result, I think, is better for customers and better for the company as well.

That's a great example of identifying something that's not working for your customers and then figuring out how to fix it.

Another example, and one of the big reasons to do this type of work beforehand, is this medical device company we’ve worked with. We were thankfully involved fairly early in their product development cycle, but it turns out that internally they misunderstood the value of their products by about a factor of two. And these aren't cheap products. We're talking hundreds of thousands of dollars.

So, the danger of not taking the time to properly understand how customers are thinking about your product and how you're creating value is that you're leaving a lot of money on the table.

The danger of not taking the time to properly understand how customers are thinking about your product and how you're creating value is that you're leaving a lot of money on the table.

Like I said before, as people interested in innovation and whose jobs depend on innovation, it’s important to understand that the money for development has to come from somewhere. If your company or your products have lower margins and lower revenue than it could, then that's all less money available for future innovation and future development.

JESSE: Yes, it’s not just about your bottom line, but about being able to fund future innovation that actually benefits your customers and drives value for them going forward.

KYLE: Absolutely!

One of the nice things about pricing done right, and especially price segmentation, so figuring out different groups of customers that value the product differently, is that you’re able to serve more customers AND make more money at the same time.

One of the nice things about pricing done right is that you’re able to serve more customers AND make more money at the same time.

Let's say the private sector is willing to pay a figure that’s up here, and academics are willing to pay something that’s down here. Figuring out a way to segment those audiences and charge both of them those prices is what it’s about. You can serve more customers and make more money. It's really a win-win for everyone.

Your company is going to get better because you have more money to pour back into innovation, and your customers are better off too because you're able to serve two different segments rather than only charging high and capturing that private side of the market and the academic side just having to figure it out without you.

By putting that segmentation strategy into your pricing, you're able to address both markets at the same time.

Examples of innovative pricing done right

One of the most interesting cases for me in the last 10 years is Dollar Shave Club. It was basically an early delivery subscription service. So, instead of buying your razors at the convenience store when you need them, Dollar Shave Club would deliver a razor to your door every month. Clearly, I would not be a target customer (Editor’s note: Kyle pointing to his beard), but I understand there are people out there who need a razor month. It’s kind of a “set it and forget it” way, you always have the razor when you need it.

What I really love about this case is that it was purely an innovation on the pricing strategy. It was merely changing something from a one-time purchase to a subscription. There wasn't anything special about the razors, they were just rebranded razors that I'm sure they bought in bulk from China, and there's nothing wrong with that.

But the value that they were creating for customers was purely from having a more convenient way to buy and to interact with the company. They were sold to Unilever for $1 billion, purely on innovating the pricing strategy, so clearly it worked out well for them.

That's something really interesting about examples like Uber as well. The core innovation there is technological, but it's also pricing. It's about how we use pricing to address modern customers’ needs better the antiquated taxi services. How do we merge this mobile device that people always have with them with this dynamic pricing to better match supply and demand and create something that's seen as really invaluable across the world?

An airline example is the US company called Southwest, which started primarily in Texas and in our Southwest, hence the name. But what’s rare about them among US carriers, is that they are actually able to command brand loyalty. There are people who are really committed to the brand.

They also have slightly different business operations. You can't reserve a seat on their flights. They fill up the plane as they go, which actually leads to faster boarding times and faster turnaround. The entire fleet is one model of aircraft, which makes maintenance and training for the pilots a lot easier. They tend to go to the tier two airports in the city rather than the main one.

But one of their big pushes is actually around pricing and price transparency. Um, so they actually have branded it as “Price Transfarency”. The idea there is that they are simply easy to buy from because they are fairly priced and don't have hidden fees.

I think that is really interesting because the implication there is that you're getting good value, you're getting good benefits for the price, but they're not actually saying that they're the lowest price – and they're usually not. But what they are saying is because we don't charge for a checked bag, because we don't have change fees, that should be worth something. You should be willing to pay a premium, implicitly, for that level of service and for that ease of working with our company.

But what they are saying is because we don't charge for a checked bag, because we don't have change fees, that should be worth something. You should be willing to pay a premium, implicitly, for that level of service and for that ease of working with our company.

So, I think that's another way in which pricing strategy is really connected well with their brand strategy. They know what type of customer they want to go for, they know what they stand for as a company and what their differentiators are, and they're figuring out how to use pricing to help tell that story, rather than cut against that story.

From our own work, I could say that it's critical to get sales teams onboard with pricing as well. Not only to get their input from the beginning, especially in terms of what customers are valuing, but also to get them onboard with this idea of selling value, rather than selling the price point. And immediately capitulating on price if there's any pushback.

So, rather than just meeting what the competition is offering, be able to tell the story of the value that your product is delivering. This is a way in which the Economic Value to Customer can come into play again.

With EVC, you’ve already built a model that tells the story of the value you're creating with real dollars and cents attached to that story. It really gives salespeople a great tool in their toolbox for telling that story back to customers, and for being able to articulate the value that they're creating.

Part of that comes down to sales incentives to make sure that the sales teams are properly incentivized and commissioned to defend price and to defend margin dollars. That can be quite a big shift for companies, having salespeople incentivized on margin contribution rather than volume, revenue, units or something like that.

At companies where we've implemented those types of schemes, one saw a 6% increase in gross margin in less than a year, which is really huge just for a change in how sales is compensated and a change in mindset.

So that's very impactful, and it's really rewarding to be able to see those types of changes in organizations once they start thinking about all the different ways in which pricing can be considered strategic, and as something that critically helps the sales team, rather than something that just gets in the way.

The pricing process for innovation & NPD

JESSE: Let’s go back a little bit and think about someone who’s now working on a new business, product, or innovation. What level of pricing precision do you think they should go in during the process?

KYLE: In the price estimation phase, as I've talked about, it’s really just a sense of do we have a profitable product here or not.

You want to bring it to a point where you can confidently say when you should pursue this project and when we should abandon it before we invest more time into it – or reassess what the product is, or who it's valid for.

So, at that point, you're looking for enough evidence to say yes, we have something here that we should keep pursuing, or it doesn't look like there's a way to sell this profitably in the end.

Once you're getting more into price clarification, that's where, especially in terms of business model development, you want to get a lot more specific about how much value you're creating for different customer segments, how much of that is capturable in price, and start getting more into the details of the commercialization and the go-to-market strategy as well, of which pricing is a critical part. The end goal of the clarification stage is to have your launch price.

So, at that point you're really getting into the nuts and bolts of how much value is being created by these different benefits. Who is that value valid for? How much of that are they willing to pay for and getting much more precise about who your competition is for different segments.

That's also the stage in which, if you have the time, the money, and the resources, to go for external sources of information. That can be voice of customer, or some of those other methodologies I talked about.

That's where you're bringing these other pieces of the puzzle into play, and using those, it's kind of a multiple lenses approach towards getting a better holistic picture of the value that you're creating and the capturable price you can get from that.

JESSE: Looking at those phases in relation to the product development cycle, the estimation then typically happens during the concept phase, and during the prototyping and development phases, you’re then working on the price clarification. Right?

KYLE: Yes. That's how I think about it.

How much effort should one put into pricing up-front?

JESSE: Great. How do you then suggest those of us, which is of course most, who have a limited budget, use that for doing pricing research. Do you think that there's a law of diminishing returns for doing that research, especially external

KYLE: We have a white paper that goes into more details on this, but at large, it really just depends on those three factors that I outlined before:

1. Revenue expectations

How large of an opportunity do we think this is? Do we think it’s relatively niche, in which case a lower time and money investment makes sense? If we think this is a really big opportunity, then improving price 1%, 2%, or 3% over millions and millions of dollars is a really big opportunity and something that's worth putting a little more time and effort into.

2. Customer count

In addition to revenue expectations, customer count plays a big factor too, especially for some of these more quantitative and statistical methods like conjoint analysis. For them, you need a relatively high number of customers to get good data back.

If this is something you're selling to three or maybe five large customers, those types of tools aren't going to be as useful in these situations.

3. Time constraints

And finally, doing good quality market research takes time. If you have a launch date in mind, or other constraints as your backstop, then you want to be able to make sure that you're hitting everything you need to hit in time.

Time is a constraint on us all, needless to say. Sometimes we simply don't have the time and need to move faster to get to market. In these cases, we just go with our best estimates and our best understanding and adjust on the fly, rather than devote all the time on the front end.

Of course, it's ideal to do more of the pre-work before the launch because again, once a price and pricing model are out there, it's a lot harder to change it. But, needless to say, once your price is out there, then you start getting a lot of really great feedback in terms of what's resonating with customers and what's not, in terms of the actual price points, the price metrics, the price models, the pricing strategy, your segmentation, your channel strategy, and your commercialization in general.

But, needless to say, once your price is out there, then you start getting a lot of really great feedback in terms of what's resonating with customers and what's not, in terms of the actual price points, the price metrics, the price models, the pricing strategy, your segmentation, your channel strategy, and your commercialization in general.

So, part of the ongoing job of pricing strategy and pricing analysis is using that information to feed back into our current understanding in our models and adjusting prices, working with the sales team, working with marketing, working with finance, and using all of that information in a continuous improvement cycle to keep getting better as we go.

No matter how much time we put in beforehand, it's never going to be perfect. So that type of post-launch follow-up and continuous work is always necessary. Just, the more we can put our best foot forward initially, the easier a job we’ll have going forward.

JESSE: Yes, and of course the markets are always shifting, it's not a static marketplace that you're in, so it does definitely make sense to pursue these continued efforts on the pricing front.

To conclude, what’s your quick summary or cheat sheet for doing pricing well?

That's a great question. I think it's about going back to the fundamentals of thinking about pricing at an earlier stage. This idea of baking profitability into your offerings by involving pricing early on in innovation and new product development, will put you ahead of a lot of the competition.

Baking profitability into your offerings by involving pricing early on in innovation and new product development will put you ahead of a lot of the competition.

Try to get a good sense of whether there is an audience out there that's willing to pay for your offerings at a point that makes it profitable for you beforehand, rather than spending a lot of time and effort in creating a wonderful product that no one wants to buy. That's everyone's worst case.

If people are interested in learning more about this, I would really encourage them to poke around our website, but also that of the international Pricing Society, and really just learn more about pricing.

Pricing has the science side, the more quantitative side, but also the art side, which again makes it really interesting for people with not just straight up business backgrounds like myself.

There's so much about psychology, organizational development and branding, how customers are behaving when they actually interact with your product and so on. Those are all critical pieces of information for pricing that are more on the art side.

Then on the science side, of course you can do, depending on the type of product and the market situation, much more statistical analysis, econometric regression and these quantitative market research methodologies that I’ve mentioned.

It's really the combination of those that make good pricing good.

Pricing is the strongest lever we have around profitability of a product or a company.

Pricing is the strongest lever we have around profitability of a product or a company. It's much better to improve pricing by 1% than to reduce costs by 1%. You have a much larger effect on the bottom line by doing a better job with pricing than you do almost anywhere else, so the overall message would be one of the centricity of pricing and the foundational support that it can be for the business, versus simply being an afterthought and something that's tacked on the product at the end.

JESSE: Thanks, we’ll put links to all of the resources that you mentioned on our website. Anything else you'd like to share with our listeners on the topic before we wrap up?

KYLE: No, I think that's about it. Thank you very much for your time Jesse, I really appreciate it. If anyone has questions, please feel to reach out to me. I'm very active on LinkedIn.

JESSE: Thank you again for coming on the show and sharing your thoughts, Kyle!

.png)