Key Innovation Management Models and Theories

Innovation management is a diverse topic with many different layers and dimensions. Although innovation itself is often seen as an abstract concept, it’s a multidisciplinary field of study that has a number of different models, theories and frameworks.

We believe that understanding the common ones helps make sense of this complex beast and can be used as reference when quantifying innovation and explaining innovation-related phenomena.

In this post, you'll learn more about innovation models that focus on:

- classifying different types of innovation

- explain common regularities

- introduce theories regarding portfolio management and the life cycle of innovation.

Although none of these models and theories have the ability to capture the essence of innovation by themselves, they each make an excellent point about innovation that we can learn from and apply to our thinking.

Table of contents

Types of innovation

Many people mistakenly assume that an organization is either innovative or not. This rather black and white approach fails to understand that there are several different types of innovation for an organization to pursue, and that there isn’t just a single correct way to innovate.

Because there are as many different classifications and typologies as there are authors on innovation, we’ll try to combine the most common terms that are used to classify different types of innovation. You'll also learn how they relate to each other.

Disruptive vs. sustaining innovation

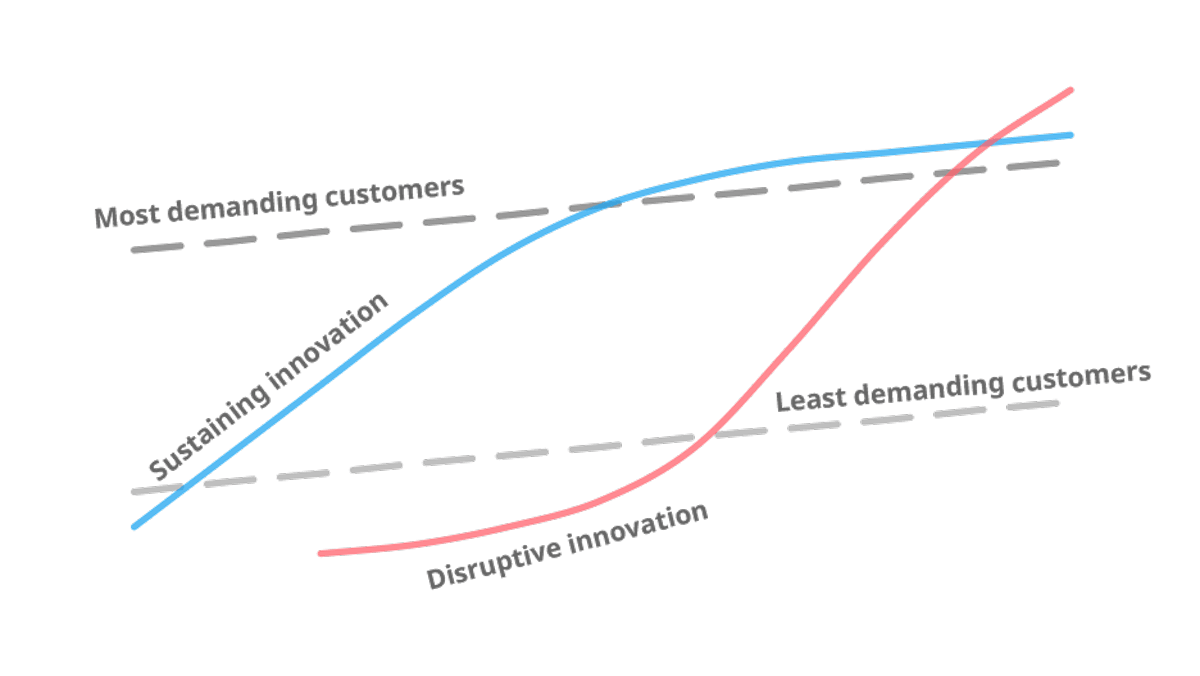

Clayton Christensen was the first to introduce the concept of disruptive innovation in 1995.

Disruptive innovation, by definition, refers to a concept, product or service that creates a new value network either by disrupting an existing market or creating a completely new market.

In the beginning of the life cycle of an innovation, disruptive innovation generally provides lower performance, and while these kinds of innovations often aren’t “good enough” to satisfy current customers, they appeal to a different market instead.

A classic example of a disruptive innovation is a transistor radio, which initially offered worse sound quality compared to those big existing ones.

Although a lighter radio wasn’t of interest of a typical customer at that time, it appealed to young travelers who enjoyed bringing music to the beach. As the sound quality improved, a portable radio challenged the conventional market, eventually displacing the heavy and bulky analogue radios.

Sustaining innovation, on the contrary, refers to the type of innovations that exist in the current market and instead of creating new value networks, it rather improves and grows the existing ones.

For example, nearly all modern cars can be considered to be sustaining innovations. If we look at for example Toyota Prius (first launched in 1997), the basic functionalities of the car have stayed pretty much the same.

It only continues getting slightly better with every iteration, continuing to cater the needs of a typical Prius customer.

Radical vs. incremental innovation

Both sustaining and disruptive innovation can be either radical or incremental.

Radical innovation happens when a new technology completely disrupts existing business or economy and creates a new business model.

Only about 10% of innovations fall into this category because they are the most difficult to execute.

Only 10% of innovations are radical.

Salesforce, for example, is often credited with being the first to invent the new cloud model for delivering software via web. Not only did it succeed in launching one of the most popular CRM software, it simultaneously developed the SaaS (software as a service) business model, completely transforming the way business has been done in the tech industry ever since.

Incremental innovation, in turn, refers to a series of small, gradually built improvements to existing products, processes or methods to maintain competitive position over time. The majority of innovations are incremental, because these types of innovations are often the easiest and most cost-efficient to implement.

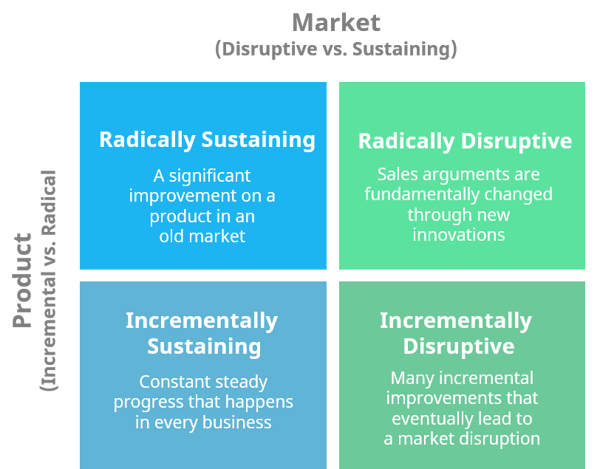

The Innovation Matrix

To clarify the aforementioned dimensions and to better demonstrate them, we took all four terms and combined them with our Innovation Matrix.

- Radically disruptive – Innovation that harnesses new technology and creates a new business model. Has no clear competitors.

- Radically sustaining – Improvement on a product or process in an existing market that provides new value for the customer.

- Incrementally disruptive – An incremental improvement in technology that leads to a dramatic disruption.

- Incrementally sustaining – Small and cumulative changes in an existing product, technology or service.

The Innovation Matrix can be used to classify the initiatives in your innovation portfolio. In case you’re looking for more detailed information of the matrix, check out our post on managing disruptive innovation with the Innovation Matrix.

Architectural vs. modular innovation

In addition to the types of innovations mentioned above, I'd also like to briefly introduce the concepts of architectural and modular innovation.

Architectural innovation is described as the reconfiguration of existing product technologies, and was introduced by Rebecca Henderson and Kim Clark in 1990.

The main point in architectural innovation is that while the core components of the product remain the same, the relationship between these components changes. This type of innovation entails the overall design, system or the way components interact.

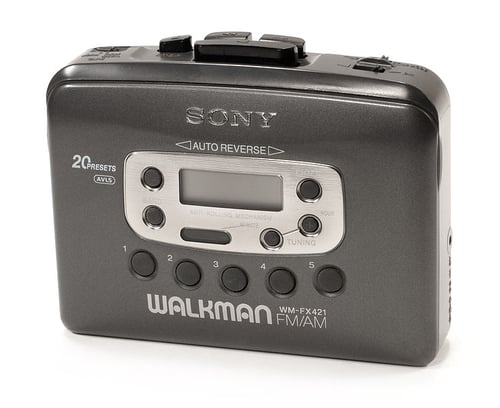

A classic example of architectural innovation is Sony Walkman, where all main components already existed, but were before just used in other products.

Modular innovation (or component innovation), on the contrary, is the exact opposite. In modular innovations, one or more components of a product is changed while the overall design stays the same.

An example of a modular innovation is a clockwork radio that is powered by an internal generator, and provides electricity for long periods of time. It uses the architecture of an established radio but has a different impact because it can be used in areas with power shortages.

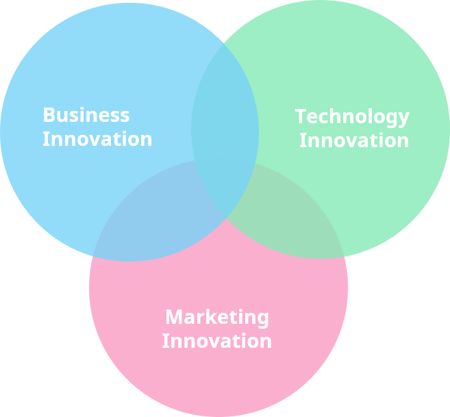

Business model, technology- and marketing innovations

While The Innovation Matrix is a solid framework for classifying innovation from the market point of view, another perspective is to look at the source of the innovation.

Usually, innovation falls into one the following categories:

Business model innovation

Business model innovation is all about the ability to rethink your current business to find new revenue streams and maintain competitive advantage. It can be done either by improving an existing business model or by looking for new ways to provide value.

Many previously successful company has failed in business model innovation because instead of envisioning possible future innovations, they've been too busy with their current operations.

What these companies should have done instead, is to have tried to actively challenge the basic assumptions and the dominant logic in the industry to find new profitable opportunities.

Luckily, business model innovation is easier when done in a systematic manner:

- Analyse your current business model – Identify your target market and your offering. How exactly is your value proposition created and your revenue generated? To do this, you can use for example the Business Model Canvas.

- Confront your current business model – Engage in ideation to challenge common assumptions and current way of doing things. Sometimes, questioning your long-held assumptions may help you to come up with those infamous “out-of-the-box ideas” especially if you’re suffering from a creative block. You can generate new ideas for example with the help of these ideation tools.

- Ensure the consistency of a business model – Make sure your new business model is consistent with your long-term vision.

- Build a pilot and test it – Make iterations based on your findings, always keeping success factors and possible pitfalls in mind.

Technology innovation

A general misconception is that innovation breakthroughs are always based on fascinating and costly technologies.

Creating positive change doesn’t necessarily require the most tech-savvy personnel or large technological investments. However, most of the great innovations still utilize new technology, in one way or another.

For many industries, technology is the major player when seeking a competitive edge and increasing profit margins.

Technological innovation means:

Generating new ideas based on technology, capability or knowledge to produce a new solution to a real or perceived need and to develop this solution into viable entity.

New technology can be used to:

- Accelerate your innovation processes

- Realize new possibilities in the market

- Generate ideas and build them into innovations

- Model your products and services for the market

- Experiment and test these new concepts

One of the best things about technology innovation is that you don’t need to start from scratch. Sometimes a technological solution that was originally intended for one purpose, might also work for a whole another use case. To do that, start by seeing if any of the new interesting technologies around you could be modified and utilized for your purpose.

Marketing innovation

For a business to succeed, marketing innovation is claimed to be as important as product innovation.

This makes sense, as there’s no point spending time and money on business model- and product development if no one is able to find it and benefit from it.

However, marketing innovation isn’t just about finding new unique channels and tactics to promote your offering but about finding new markets and creating new value propositions that others aren’t able to (or do not want to) provide.

This can be done by launching your technology, product or business model in new unconventional places or by promoting your existing offering in a way it hasn’t been promoted before.

Classic marketing innovations are such where an existing product is used to a whole new purpose and it provides a different value proposition for a completely new segment.

For example, if you simply happen to have a large inventory of products you want to get rid of, finding new ways to use them and promote them might be worth giving a shot.

Consider revisiting your marketing tactics on a regular basis, especially if you feel like your existing marketing strategies and initiatives aren’t effective enough to generate desired results.

Ten types of innovation

Another model that classifies innovation based on similar sources is Doblin’s Ten Types of Innovation.

The model describes itself as The Discipline of Building Breakthroughs and aims to provide a way to identify new potential opportunities beyond products and revisit existing strategies to develop viable innovations.

The ideology behind these types of innovations is that building new products isn’t the only way to innovate and might actually provide the lowest return on investment with minimum competitive advantage.

Instead of solely focusing on developing different features of the product, the ten types of innovation-framework approaches innovation in a more holistic way, claiming that the best results can be achieved when all of the following categories are considered.

%20.png?width=1686&name=Ten%20types%20of%20innovations%20(1)%20.png) The three main categories of this model are:

The three main categories of this model are:

- Configuration

Comprises your profit model, networks, structures and processes. In other words, your business model. - Offering

The offering-category includes distinguishing features and functionalities as well as complimentary products and services related to your system, referred to as your technology. - Experience

The experience, consists of all the channels through which your offerings are delivered to your customers and users, as well as your brand, service and other distinctive interactions with your customers, also known as your marketing.

A concrete example of a company that has succeeded in all of the aspects is Airbnb. With its high-end alternative, Airbnb Plus, they’ve managed to improve both their offering and experience, providing better value for existing and new customers.

Just like Airbnb, if you are able to combine and improve all of the aforementioned aspects in one innovation, great. If, however, you’re only focused on making improvements in one area, there is an increased risk that someone will do it better.

In a sense, the ten types of innovation model can be used as a scale to evaluate which aspects to improve on and can give you concrete examples that aren’t only focused on product or technology innovation. If you’re looking for more tips for how individual ideas can be evaluated, have a look at our previous post about the topic.

Innovator’s Dilemma

Innovator’s Dilemma, one of the most significant and widely recognized theories in history, is designed to explain psychological and economic phenomenon regarding disruptive innovations.

The core of the dilemma

In the beginning, innovation, and most specifically disruptive kind, is inferior to the existing products and services on the market. Because product improvement takes a lot of time and requires multiple iterations, the value for the customer is minimal, at the bottom of the S-curve.

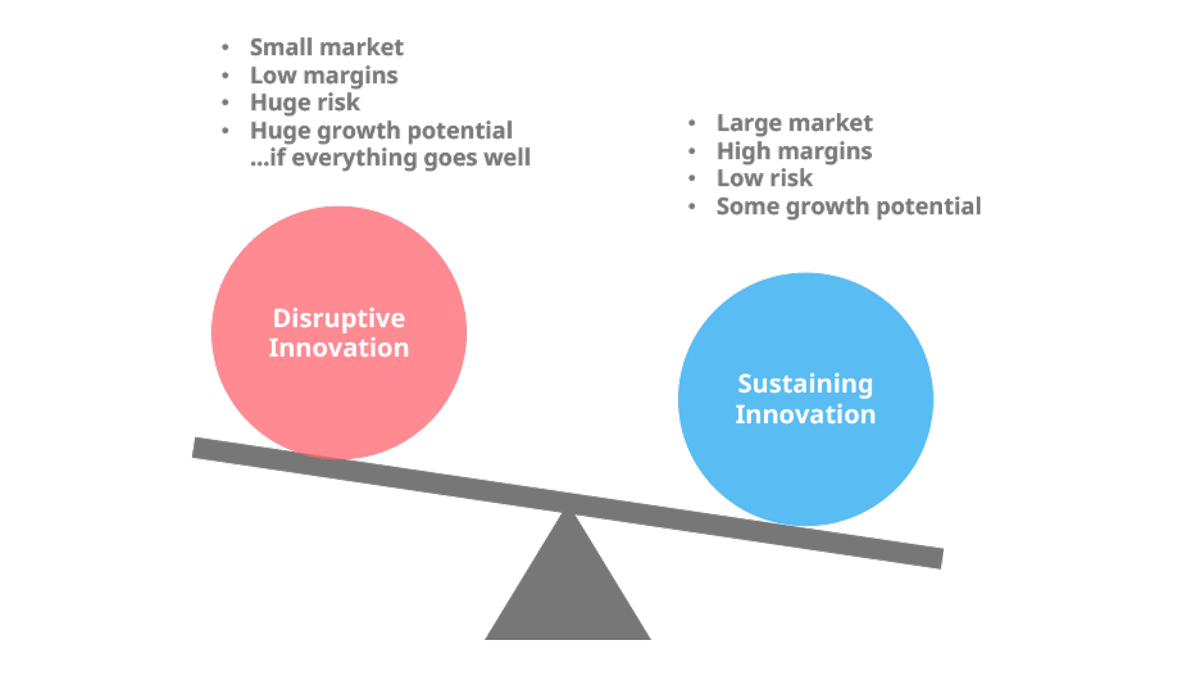

While disruptive innovation initially caters only to a small and not-so-profitable customer base, the incumbents are focused on serving more demanding, high-end customers using their existing value channels.

This is where the company typically has higher profit margins, which is why established companies with rational decision-making processes usually choose not to invest in disruptive initiatives in the early stages. Once the disruptive innovation enters the mainstream, the established companies typically pick up on them again. At that point, however, it’s often too late since the new entrant is on the exponential part of the S-curve, which makes catching up quite unlikely, even with the additional resources the incumbent has at their disposal.

Once the disruptive innovation enters the mainstream, the established companies typically pick up on them again. At that point, however, it’s often too late since the new entrant is on the exponential part of the S-curve, which makes catching up quite unlikely, even with the additional resources the incumbent has at their disposal.

The reason for this problem isn’t because the incumbents fail to develop disruptive technologies. Instead, the problem occurs when incumbents attempt to apply new technologies to their existing value networks or reject moving into new markets because they are seen as too small to drive growth goals or are simply perceived to have too low margins.

If you want to make innovation happen in an established organization, the best way to do so is to treat your innovation project as a separate unit.

Because the business model and growth expectations of disruptive innovation are different, the only way to succeed is to set up separate processes and rethink your ways of working so that they don’t interfere with your core business.

Jobs-To-Be-Done Framework

Jobs-To-Be-Done is a theory and a methodology made popular by Strategyn that focuses on Outcome-Driven Innovation. The fundamental idea of the theory is that people buy products and services to get jobs done, and while different products and services come and go, the underlying job-to-be-done stays the same.

After all, regardless of the chosen business model or tactics, each company is looking for ways to identify opportunities for growth.

"People do not want a quarter-inch drill, they want a quarter-inch hole."

– Theodore Levitt

The difference between traditional innovation and outcome-driven innovation is that most traditional innovations are just improved versions of existing products, whereas outcome-driven innovations are more focused on the job that needs to get done.

This outcome-driven approach allows you to learn more about customer's needs and which of those are unmet.

According to a study that was conducted by the creators of this framework, nearly 86% of outcome-driven innovations are successful, whereas only 17% of traditional innovations succeed.

The reason for this is that outcome-driven approach directly addresses specific metrics the customer has in mind that define the successful execution for the job.

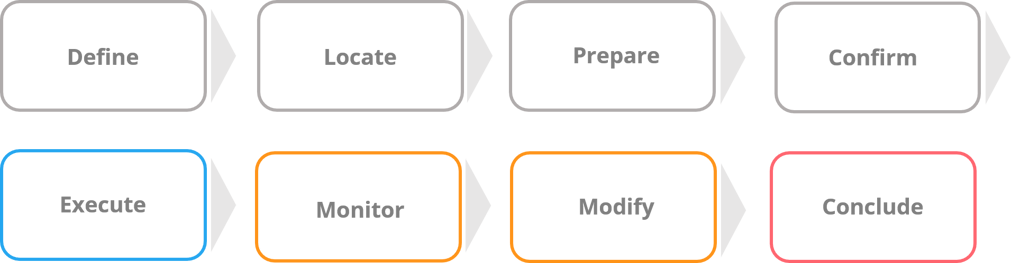

The Job Map

The Job-To-Be-Done framework suggests that all jobs consists of eight different steps, where you look for opportunities to help your customers.

The so-called "Job Map" is simple and straightforward:

- Define your customers goals and resources.

- Locate what information is needed to do the job.

- Prepare the environment where the job will be done.

- Confirm that your customer is ready to get the job done.

- Execute the job.

- Monitor the job so that it's successfully executed.

- Modify and make alterations to improve execution.

- Conclude the job or repeat.

Each of the eight steps focuses on addressing the job-to-be-done correctly. The job is at the heart of the whole innovation process all the way from planning to execution.

The Jobs-To-Be-Done method works quite well for identifying your target market and segment. It's obvious that if there's a job that your customers aren't struggling to get done, there might not be any point to go after that market.

The technology adoption life cycle

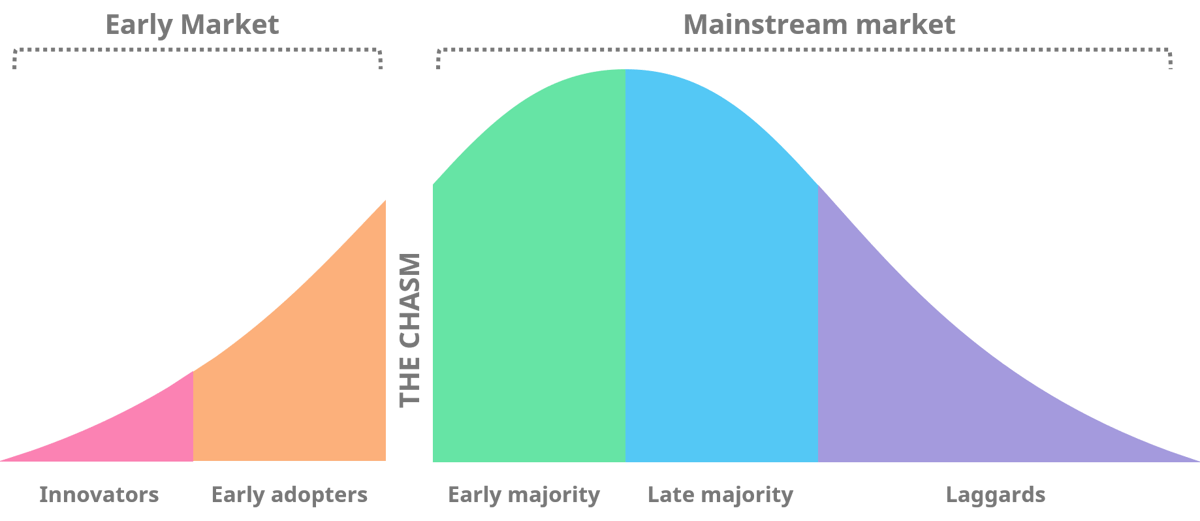

The Technology adoption life cycle was first introduced by Geoffrey Moore in his book Crossing the Chasm.

It builds on the research on one of the most researched social theory, the diffusion of innovations among individuals and organizations, created by Everett Rogers in 1962, and explains why companies with disruptive products and technology often have difficulties to succeed in the mainstream market.

Diffusion of innovations

The diffusion of innovations is traditionally defined as the process by which an innovation is communicated through certain channels over time among the members of a social system.

These channels can be any channels through which information is transmitted, all the way from interpersonal communication channels to mass media. The diffusion theory attempts to identify the aspects that influence the rate of adoption of an innovation.

According to the theory, the main aspects that affect the distribution of a new idea or innovation are time, communication and social systems, also referred to as adopter categories.

A more specific definition of adopter categories is ‘individuals, organizations or larger clusters within a social system on the basis of their innovativeness’.

The adopter categories are:

- Innovators – People who are enthusiastic about new technology and have a high risk tolerance. They are keen to be the first ones to try out a new technology and allow to adopt innovation, even if it might eventually fail.

- Early adopters – More discreet in their adoption choices compared to innovators, but appreciative to potential products that may give them or their organization a competitive advantage.

- Early majority – People who adopt an innovation after a significantly longer time compared to innovators or even early adopters. Makes up the majority of the market.

- Late majority – Adopt an innovation after the average participant, extremely cautious and willing to see proof of results and usefulness before buying.

- Laggards – The last ones to adopt an innovation. Extremely skeptic and will buy a new technology only if they really must.

In addition, the following factors have been identified to affect the adoption rate of the innovation in the market:

In addition, the following factors have been identified to affect the adoption rate of the innovation in the market:

- Compatibility – is the innovation perceived to be consistent with the needs of potential adopters?

- Relative advantage – is the innovation perceived to outperform the competition?

- Complexity – is the innovation easy to understand or does the adoption process require new knowledge and skills?

- Trialability – can it be experimented before purchasing?

- Observability – are the benefits visible for others?

Crossing The Chasm

Moore believes that the most difficult transition is from the early adopters to early majority, referred here as the chasm. The chasm occurs because the expectations between these two adopter categories are significantly different.

The basic idea is that the entire market can be represented with a bell curve that can be divided into segments based on how eager the customers are to adopt new technology with each segment having their own sets of expectations and desires.

The left side of the curve, the early market, consists of people who want the newest inventions, whereas the ones on the right, in the mainstream market, are more interested in real, convenient solutions.

The early market type is typically expecting intuitive solutions and are often motivated by future opportunities. The mainstream market, however, is more analytic and willing to bear smaller risk, whereas the late majority is usually motivated by real-life problems that are present at the moment. Typically, people who fall into this category only want to pursue things that are extremely likely to happen.

For companies to be able to cross the chasm, they need to find new ways to make their products more attractive in the eyes of the early majority.

Developing the product and changing the way you talk about it to suit the majority can often mean making compromises that alienate the innovators and the early adopters that allowed your early success. This can be a very painful process that many companies find difficult, not only psychologically, but also in practice.

The best way to win over the mainstream is to focus on segmentation and do it extremely well. Here’s a few tips:

1. Vertical vs horizontal – define your target market and brand yourself as a specialist in that specific niche. This obviously won’t work if your business idea is to provide a single solution for all types of users. Either way, you must pick either one as you cannot provide everything for everybody.

2. Focus on one niche at a time – Use the Bowling Alley strategy make sure you dominate the early market niches before moving to the adjacent ones.

3. Acknowledge differences – Make sure your product, pricing and distribution meets the expectations of the mainstream market.

This concept is very closely linked to the innovator’s dilemma. If you are able to make the leap, you are likely to be able to have a more scalable, and often a more profitable business, as the majority is where the economies of scale start to kick in.

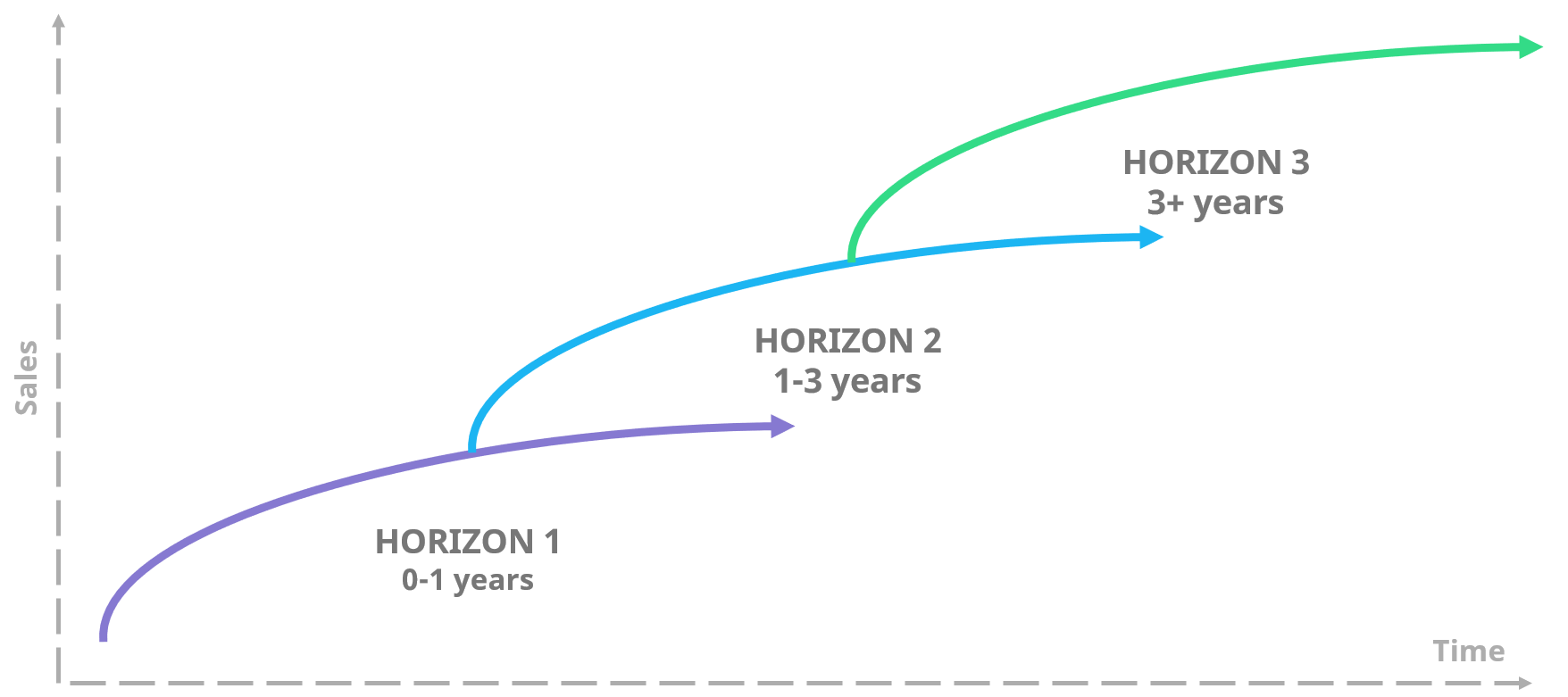

The Three Horizons of Growth

The three horizons of growth, created by McKinsey & Company, is a well-known model for organizations to structure their initiatives and finding an appropriate balance between short- and long-term projects in their portfolio.

The point of the three horizon model is that for an organization to maximize their growth potential, they need to simultaneously work on projects within all three horizons:

- Horizon 1: Initiatives related to the core business

- Horizon 2: Development of new opportunities in emerging businesses

- Horizon 3: Creation of new, transformational businesses

Same happens if you only focus on creating disruptive innovation and disregard your current core business, the one that is successful today.

To maximize growth potential, you need to simultaneously work on projects for all three horizons.

You can’t guarantee a bright future without a balance between all of the three horizons and by finding that, you’ll not only maximize your growth potential, but also decrease the risk of your business portfolio.

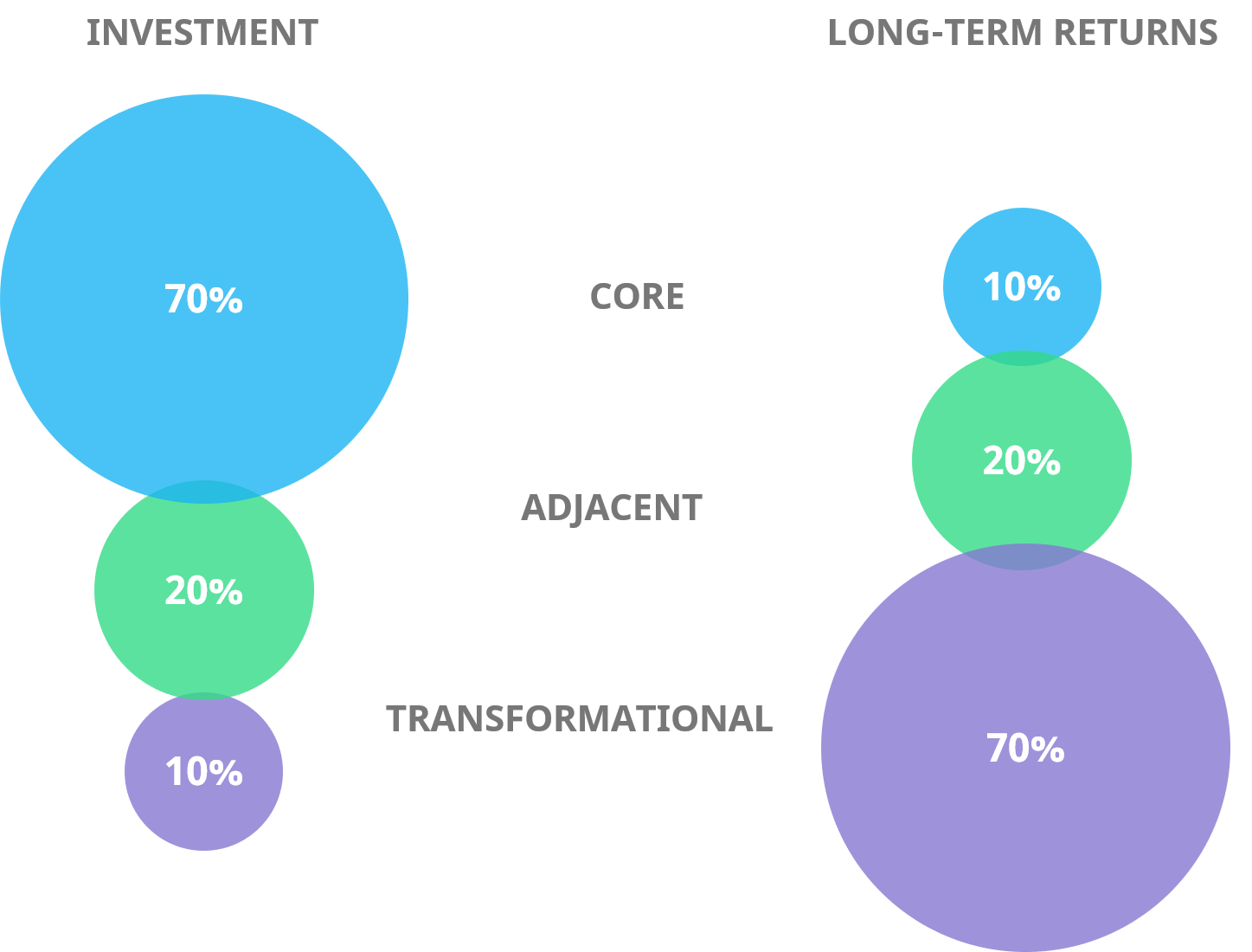

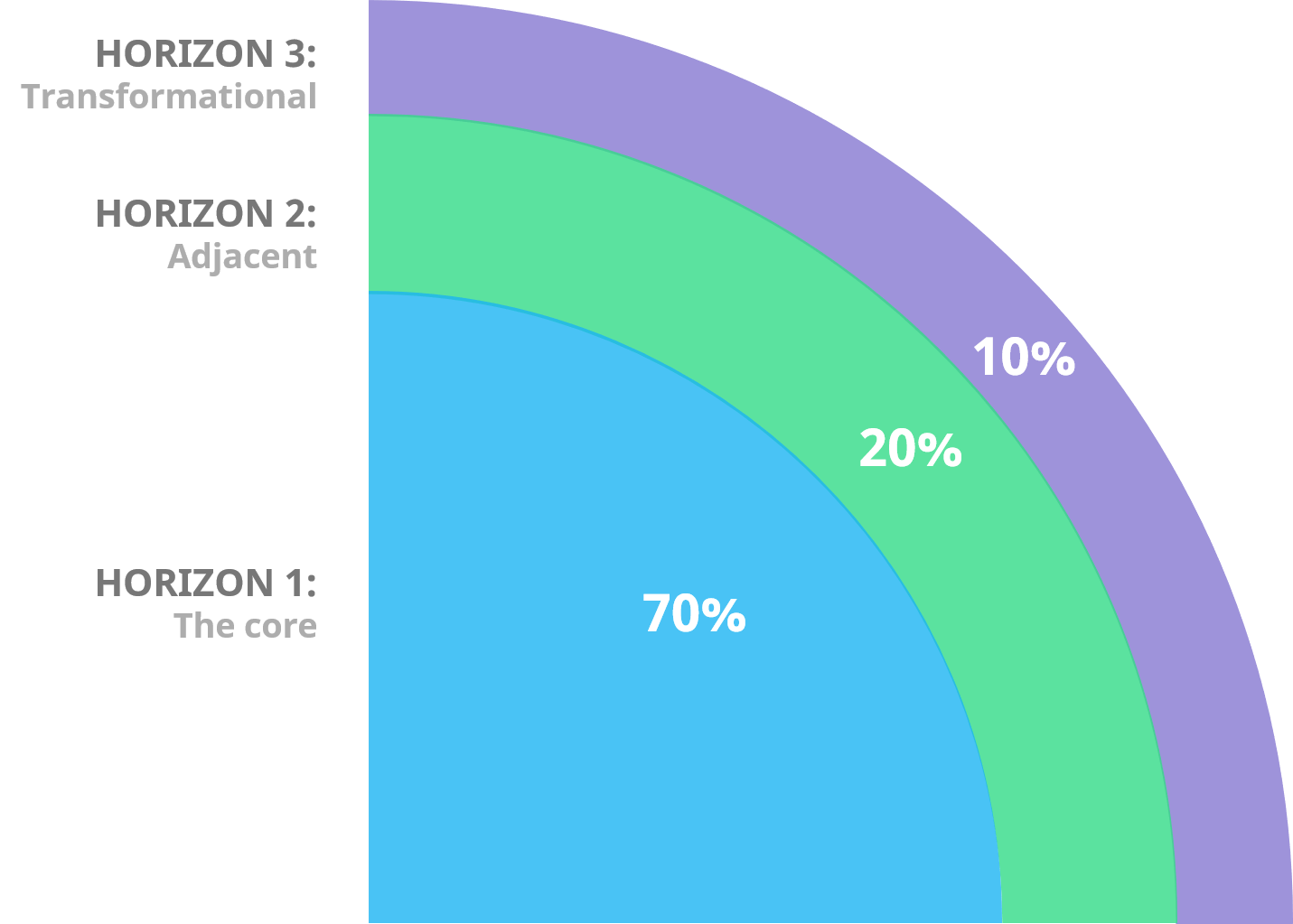

70-20-10 Rule

To put the three horizons model into practice, you can use the 70-20-10 rule, pioneered by then Google CEO Eric Schmidt, which is a simple rule for allocating resources between “the core”, “the adjacent” and “the innovative stuff”, often referred to as “the transformational”.

Here the core refers to the activities that make up the majority of existing business, whereas the adjacent means new improvements and logical extensions for the current business. The transformational, however can mean anything brand new for the organization that isn’t related to the core.

To get the best possible result, try to allocate 70% of your resources on the core business initiatives, 20% on projects related to your business, such as new markets, and the rest 10% on creating something completely new.

In addition to anecdotal evidence from Google, later research, has also seemed to confirm that companies that allocate their resources in this manner, typically outperform their peers by a margin of 10-20% (measured with their P/E ratio). The research also identified that the long-term returns for each type of investments are actually the inverse of the resources invested.

Because the three horizon model of growth and the 70-20-10 rule are talking about the exact same thing, we can combine these two for a more practical look at the issue. Having said that, 70-20-10 is not a rule every business should adopt. It all really depends on your circumstances and strategic decisions, and a different allocation can prove to be much more suitable for you. However, the 70-20-10 rule is simply a highly practical and reasonable starting point for most organizations.

Having said that, 70-20-10 is not a rule every business should adopt. It all really depends on your circumstances and strategic decisions, and a different allocation can prove to be much more suitable for you. However, the 70-20-10 rule is simply a highly practical and reasonable starting point for most organizations.

Conclusions

Understanding some of the commonly accepted innovation models and theories helps make sense of the complex topic.

While none of them are able to capture the essence of innovation alone, and although some of the models can be (and have been) criticized, they form a pretty good overview of the subject.

However, understanding all of these models is just a beginning of successful innovation. When you know what is certain, the next step is to put this knowledge into practice since action is what really makes a difference and is the only way to learn. To do so, use your own heuristics and keep an eye on the others

”An ounce of action is worth a ton of theory.”

– Ralph Waldo Emerson

Innovation is both an art and a science. Both dimensions are needed and both of them has to be studied and learned separately to be able to build a systematic approach towards innovation.

So, when you feel confident with the knowledge you’ve acquired regarding innovation management models and theories, try to see if you can implement some of the points to your own work.

You can get started with innovation with our Ultimate Toolkit for Innovation Management that includes over 15 of our favorite tools, templates and guides for managing innovation. You can use the toolkit for planning your strategy, building innovation processes and generating more ideas in your organization.

And, don’t forget to subscribe for more of our upcoming articles!

This post is a part of our Innovation Management blog-series. In this series, we dive deep into the different areas of innovation management and cover the aspects we think are the most important to understand about innovation management.

You can read the rest of the articles in our series covering innovation management by clicking on the button below.